I. Introduction

Energy poverty is an important factor affecting women’s ability to access decent employment opportunities, influencing their ability to lead the life they value (Alkire, 2005). It refers to a lack of access to modern energy services in households (Nussbaumer et al., 2012), including electricity, cleaner fuels for cooking, heating and cooling, and powering essential devices for clean water, entertainment, information, and communication (Gupta et al., 2020). Despite efforts by policymakers, energy poverty remains widespread in India, affecting at least 50% of households in 22 out of the 35 states and union territories (Gupta et al., 2020). This situation impacts women’s health, education, and time use patterns (Winther et al., 2017), thereby limiting their capability to secure decent employment. The low rate of decent employment among women hinders the achievement of SDG 8 and other related SDGs (Ara, 2021). Therefore, promoting decent employment among women in India is essential for sustainable development.

In recent years, the government has undertaken significant efforts to address both demand and supply-side bottlenecks to enhance decent employment opportunities for women (Ara, 2021). Nevertheless, ‘inequality of opportunity’ (Roemer & Trannoy, 2015) continues to be a substantial impediment that hinders the rapid increase in their coverage of decent employment (Vega et al., 2011). Roemer (1998) introduced the concept of ‘equality of opportunity,’ which posits that an individual’s outcome should not be influenced by factors beyond their control. Inequality of opportunity occurs when women are denied access to decent employment, not based on their abilities, but due to variables such as religion, caste, economic status, and the gender of the household head. Given that women comprise approximately half of the population and their advancement has a significant intergenerational impact, the failure to promote equality of opportunity can result in the intergenerational transmission of poverty and inequality, thereby impeding the country’s development progress. This paper aims to investigate the influence of energy poverty on women’s access to decent employment opportunities in India and its states. Utilizing the ‘Human Opportunity Index’ methodology (Vega et al., 2011), we estimate the ‘Dissimilarity Index’ to measure inequality of opportunity and apply Shapley decomposition of the D-index to quantify the contribution of energy poverty to overall inequality of opportunity.

This study presents three main contributions to the existing literature. First, it is the initial study to evaluate how energy poverty impacts decent employment rather than just employment in India and its major states. According to the UN’s ‘decent work’ agenda, regular and sustainable employment is promoted, and thus, regular employment is considered a decent employment indicator (ILO, 1999). Second, previous research (Choudhuri & Desai, 2020; Winther et al., 2017) used electricity or cooking fuel as proxies for energy poverty, which may not capture the full scope. This study employs a multidimensional approach to measure energy poverty. Third, the study examines the impact of energy poverty on regular employment across 32 sub-samples based on marital status, place of residence, and education level.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section II presents the theoretical framework, followed by a discussion of the methodology and data in Section III. Section IV outlines the main findings, and the final section provides the conclusion of the study.

II. Theoretical Framework

Traditional social norms often assign women the majority of household tasks, including cooking, cleaning, and caring for children and the elderly. Energy poverty imposes additional burdens on them as they spend significant amounts of time gathering water, firewood, coal, and cow dung from local sources (Pachauri & Rao, 2013). The lack of basic electrical appliances such as washing machines and refrigerators increases the time required for cooking and cleaning (Sadath & Acharya, 2017). Additionally, caregiving responsibilities for children and the elderly are more time-consuming without modern energy services, exacerbating time poverty. This time poverty, in turn, restricts women’s access to education, information, and self-care.

Furthermore, women who engage in cooking under conditions of energy poverty are exposed to indoor air pollution and extreme temperatures (Sadath & Acharya, 2017), heightening their risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (Pan et al., 2021). The combined loss of time, health, access to information, and educational opportunities ultimately hinders women’s ability to secure regular employment.

While energy poverty contributes to inequality of opportunity, its severity is expected to vary based on place of residence, marital status, and education level. For example, since education enhances the ability to secure decent employment, it is anticipated that women with no or low levels of education will experience greater inequality of opportunity compared to those with higher education. A similar argument applies to place of residence and marital status. In rural areas, employment is predominantly in the agriculture sector, often as self-employed individuals or casual laborers. In contrast, urban areas offer better infrastructure and a wider range of employment opportunities, allowing women to obtain more stable jobs. Consequently, it is reasonable to expect that women in rural areas will face greater inequality of opportunity than their urban counterparts, given the same level of education. Additionally, the issue of time poverty, which arises from energy poverty, is more pronounced among married women due to their additional household and childcare responsibilities. Therefore, to accurately assess the overall inequality of opportunity and the contribution of energy poverty, factors such as place of residence, marital status, and education should be considered.

III. Data and Methodology

A. Data

The study utilizes secondary data from the fifth National Family and Health Survey (2019-21). The sample consists of 31,611 employed women aged between 15 and 49 years. The NFHS categorizes employment into three types: ‘throughout the year’, ‘once in a while,’ and ‘seasonal’. The dependent variable is regular employment, serving as a proxy for decent employment. A woman is considered regularly employed if she is employed throughout the year and not seasonally or sporadically. Independent variables include age, sex of household head, religion, caste, and energy poverty.

The NFHS provides data on all independent variables except for energy poverty categorization: ‘not energy poor’, ‘vulnerable’, ‘acute’, and ‘severe’, which need to be constructed using the survey’s relevant indicators. Based on the literature on multidimensional energy poverty, six dimensions of energy service were considered: cooking (modern cooking fuel and indoor air pollution), lighting (electricity), education/entertainment (computer, radio, TV), space cooling (fan, AC/cooler), productivity (fridge, washing machine), and communication. The cooking dimension has a 0.4 weight, divided equally between its two indicators. Lighting weighs 0.2, and the remaining four dimensions each receive a weight of 0.1, distributed equally among their respective indicators. Following Nussbaumer et al. (2012), the multidimensional energy poverty score is calculated for each woman in the sample.

B. Methodology

We used the World Bank’s Human Opportunity Index (HOI) methodology, which is an equality-sensitive coverage rate based on Roemer’s (1998) concept of “equal opportunity”:

\[HOI = C(1 - D) \tag{1}\]

It includes the coverage rate (C) and the dissimilarity index (D-index). C measures regular employment coverage, while D-index assesses overall inequality of opportunity caused by circumstance variables. To achieve universal coverage of regular employment, HOI advocates for indicating no inequality of opportunity. Additionally, the Shapley decomposition of D-index estimates the contribution of circumstance variables to overall inequality of opportunity. For a detailed exposition on HOI methodology, refer to Vega et al. (2011).

IV. Result and Discussion

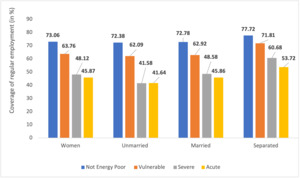

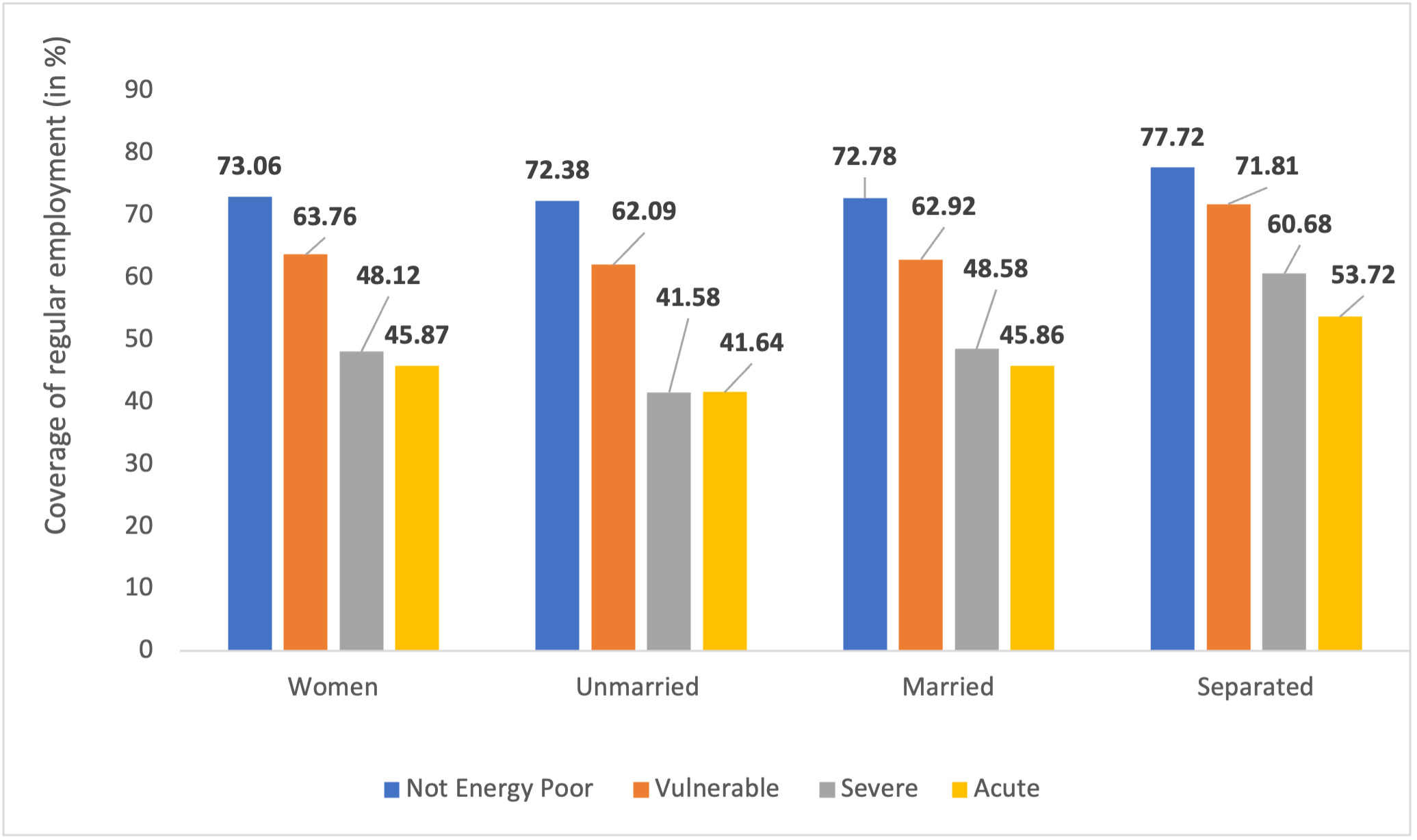

We commence by exploring the relationship between energy poverty and regular employment. Figure 1 illustrates a negative correlation between levels of multidimensional energy poverty and the probability of regular employment. Given that the distribution of regular employment also varies with other individual and household characteristics, Figure 1 merely suggests a directional relationship between energy poverty and decent employment, aligning with theoretical and empirical findings.

To quantify the role of energy poverty, we first estimate the overall inequality of opportunity, as indicated by estimates of the D-index. Subsequently, we employ Shapley decomposition to determine the contribution of multidimensional energy poverty to the overall inequality of opportunity. The estimates of the D-index and Shapley decomposition are presented in Table 1.

We observe a prevalence of inequality of opportunity in access to regular employment across various socio-demographic segments. Table 1 further illustrates disparities in the magnitude of inequality of opportunity as well as the coverage of decent employment across different education levels, marital statuses, and between rural and urban areas. The HOI increases with education level in both rural and urban regions. Additionally, considering marital status and education, the HOI in rural areas is lower than in urban areas, indicating a rural-urban divide in equitable access to decent employment. For instance, the HOI for unmarried women in urban areas is 66.1%, more than double that in rural areas (31.4%) among those with no education. This rural-urban divide is attributed to relatively low coverage and high inequality of opportunity in rural areas.

Shapley’s decomposition analysis indicates that multidimensional energy poverty significantly contributes to inequality of opportunity, often accounting for over 50% of total inequity. This underscores its critical role in determining women’s access to decent employment. The intensity of energy poverty’s impact varies with marital status, education, and place of residence. Among women of different marital statuses, the proportion of energy poverty is highest for married women in both rural (72.5%) and urban areas (73.6%), compared to only 12.9% for unmarried women in rural areas. However, with higher levels of education, the proportion of energy poverty as a discriminating factor for married women decreases to 51% in rural areas and 5.6% in urban areas. This decline is even more pronounced for separated women (1.5%). These findings highlight the significant role of education in mitigating the effects of energy poverty, particularly in urban settings.

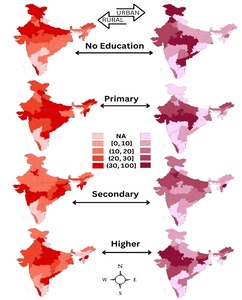

To ensure robust analysis, we conducted Shapley’s decomposition of the D-index for major Indian states. Figure 2 shows a heat map indicating that energy poverty accounts for at least 20 percent in most states, especially in Eastern, Western, Northern, and North-eastern India.

V. Conclusion

The study highlights the significant role of energy poverty in influencing women’s access to decent employment in India and its states. The analysis indicates that multidimensional energy poverty substantially contributes to inequality of opportunity in accessing decent employment. It also identifies disparities in the intensity of impact of energy poverty across education levels, marital status, and the rural-urban divide. Therefore, the study suggests a multi-faceted targeted policy approach that combines initiatives to reduce energy poverty with the expansion of decent employment opportunities and women’s education and skill development.