I. Introduction

Urban sprawl, characterized by the uncontrolled and often unplanned expansion of urban areas into surrounding rural landscapes, has emerged as a critical environmental challenge on a global scale (Hilili et al., 2024; Tule et al., 2024). This phenomenon, often driven by population growth, economic aspirations, and inadequate urban planning, leads to significant ecological consequences (Akadiri et al., 2022). The West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ) region, experiencing rapid urbanization, is particularly susceptible to these adverse impacts. In WAMZ, urban sprawl is not merely a byproduct of development but a critical issue that demands urgent attention due to its environmental and socio-economic repercussions.

While the economic benefits of urbanization in WAMZ (Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Liberia), such as increased employment opportunities, enhanced infrastructure, and improved access to services, are undeniable, the concomitant environmental costs are increasingly alarming. Urban sprawl in this region has been linked to a range of environmental issues, including air and water pollution, deforestation, and the loss of biodiversity (Akadiri et al., 2024). The expansion of urban areas often leads to the encroachment on natural habitats, disrupting ecosystems and contributing to climate change (Johnson, 2018). Moreover, the spread of urban areas often exacerbates the challenges of waste management and leads to increased carbon emissions, further intensifying the region’s vulnerability to environmental degradation (Smith & Brown, 2020).

This study aims to examine the intricate relationship between urban sprawl and environmental sustainability within the WAMZ region from an institutional perspective. The role of institutional frameworks, policies, and governance structures in shaping urban development patterns cannot be understated. Effective governance is crucial in managing urban growth and ensuring that it aligns with sustainable development goals. However, in many WAMZ countries, weak institutional capacity, a lack of coordination among different levels of government, and inadequate enforcement of environmental regulations have contributed to unsustainable urban expansion (Nguyen et al., 2019).

In this study, we employ a first-generation panel data approach using data over the period 2002 to 2022. Findings confirm that institutions have a direct effect on environmental sustainability; however, their mediating role in mitigating the impact of urbanization on the environment remains insignificant. Thus, we are of the opinion that further efforts are needed to enhance institutional mechanisms specifically aimed at managing the adverse effects of urbanization on the environment, especially for the sampled region.

II. Literature Review

The nexus between urban sprawl and environmental sustainability has been extensively explored in global literature. However, the specific context of developing regions, such as WAMZ, presents unique challenges and opportunities (Akadiri & Akadiri, 2020; Joshua et al., 2024). While there is a growing body of research on urban sprawl in Africa, the focus on the WAMZ region remains limited. Existing studies primarily concentrate on individual countries within the region with limited attention to regional patterns and interconnections. For instance, (Adeleye et al., 2019) examined the drivers of urban sprawl in Nigeria, while (Danso et al., 2021) analyzed the environmental impacts of urbanization in Ghana. While some research has touched upon the role of governance and policy in shaping urban development patterns (see Kennedy, 2012; Sorensen, 2011), a comprehensive analysis of the institutional factors driving urban sprawl and its environmental consequences in the region is still lacking. By building upon the existing literature and addressing these research gaps, this study aims to make a significant contribution to the understanding of urban sprawl and environmental sustainability in the WAMZ region.

III. Data and Methodology

A. Model specification

To evaluate the role of institutions in the urbanization-environmental sustainability nexus in WAMZ, we follow the empirical literature (as in U. F. Akpan & Abang, 2015; U. F. Akpan & Atan, 2016; Ali et al., 2019; Gaiya et al., 2024; Hilili et al., 2024) to specify our model as follows:

EVSit=α+β1URBit+β2INSTit+X′itθ+ηi+λt+εi,t

Where represents environmental sustainability indicator, represents urbanization, is the institutional quality indicators, is a vector of control variables (namely economic activities and trade openness), captures the unobserved country-specific heterogeneity effects, captures the time-specific fixed effects, and is the error term with its well-behaved properties.

To evaluate the indirect impact of institutions on environmental sustainability in WAMZ, we introduce interaction terms in Equation (1) as follows:

EVSit=α+β1URBit+β2INSTit+β3(URBit×INSTit)+X′itθ+ηi+λt+εi,t

The coefficients and capture the direct and indirect effects of institutions on environmental sustainability. The direct and indirect effects of institutions on environmental sustainability are captured through interaction terms, with the model also accounting for country-specific heterogeneity and time-specific effects.

B. Data

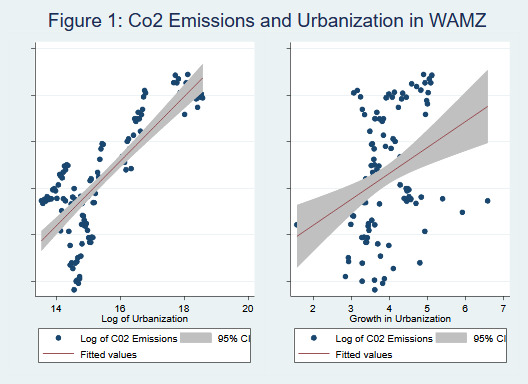

The World Development and Governance Indicators database provided the data for all variables except CO2 emissions, which came from Ritchie et al. (2023). CO2 emissions, urbanization, and six institutional measures (COC, GOVE, REG, VOICE, POL, and ROL) were used as proxies for environmental sustainability and institutions. Economic activities and trade openness were included as control variables. All variables except institutional ones were natural log-transformed for interpretation. Urbanization’s impact on environmental sustainability depends on its management. Strong institutions are expected to positively influence environmental sustainability, while economic activities can have both positive and negative effects. Trade openness may complicate the relationship between economic activities and environmental sustainability due to the pollution haven hypothesis (see Figure 1).

IV. Main Results

Table 1 presents the main estimated results excluding the interaction term. Across all models (1-12), both random and fixed effects were validated as indicated by the p-values of the respective tests. However, the p-values from the Hausman test favor the fixed-effect model as the more appropriate choice. The findings from the fixed-effect models provide strong evidence that institutions significantly influence environmental sustainability in WAMZ. Most institutional quality measures yielded negative and significant coefficients, suggesting that improvements in institutional quality are associated with reduced environmental degradation. This aligns with the findings of Akpan & Kama (2023) and Gaiya et al. (2024). Notably, government effectiveness was the only institutional measure with an insignificant impact. Additionally, the results reveal that urbanization in WAMZ is a major contributor to environmental degradation, underscoring the need for effective urban planning and environmental governance (Akadiri et al., 2024; Tule et al., 2024).

The results in Table 2, where interaction terms were introduced, indicate that institutions in WAMZ do not exhibit the expected mediating effect on the detrimental impact of urbanization on the environment. This suggests that while institutions are important for environmental sustainability, their ability to mitigate the negative effects of urbanization may be limited, revealing potential weaknesses in institutional effectiveness. These limitations may arise from inadequate enforcement of environmental regulations, insufficient resources, or ineffective governance structures. Strengthening institutions and enhancing their capacity to implement and enforce sustainable urban planning and environmental protection measures may, therefore, be crucial for improving environmental outcomes in WAMZ.

In our robustness check, we followed the approach of Gaiya et al. (2024) by constructing a composite index for institutional quality through principal component analysis (PCA), incorporating all six institutional measures used in the baseline models. The re-estimated model using this composite index yielded results consistent with our baseline findings, as shown in Table 3. The analysis confirms that institutions have a direct beneficial effect on environmental sustainability. However, their mediating role in mitigating the impact of urbanization on the environment remains insignificant. This suggests that further efforts are needed to enhance institutional mechanisms specifically aimed at managing the adverse effects of urbanization.

V. Conclusion

The findings of this study provide compelling evidence for the significant influence of institutions on environmental sustainability within the WAMZ region. The empirical results consistently demonstrate that improvements in institutional quality are associated with reduced environmental degradation. Based on these findings, we propose the following policy suggestions. First, this region should invest in capacity-building programs to enhance the ability of WAMZ countries to develop, implement, and enforce effective environmental policies and regulations while strengthening governance structures, promoting transparency, and accountability in environmental management to enhance institutional effectiveness. Additionally, WAMZ should develop and implement comprehensive sustainable urban planning strategies that incorporate environmental considerations into urban development processes. Second, policymakers should increase investments in environmental infrastructure, such as waste management systems, wastewater treatment facilities, and public transportation, to mitigate the environmental impacts of urbanization. The region should encourage sustainable consumption and production practices through awareness campaigns, education, and policy incentives. Lastly, it is crucial to foster regional cooperation and knowledge sharing among WAMZ countries to address common environmental challenges and promote sustainable development.