I. Introduction

The effect of global oil market shocks on macroeconomic fundamentals, including monetary policy targets, has been the subject of much research. Recent studies documented in this area, as shown in the works of Algozhina (2022) and Coletti et al. (2021), are, for instance, indicative of the importance of oil shocks to economic stability for both net importing and exporting countries. Meanwhile, there is a long-standing argument by Bernanke et al. (1997) that reactionary monetary policy to inflationary pressures triggered by oil price shocks amplifies the decline in output. However, this significantly departs from Kilian & Lewis (2011), who dispute that monetary policy was reactionary during the oil shock or that it was the underlying amplifier of output instability. Despite the ongoing studies in this area, there is a significant gap regarding how real oil price shocks associated with changes in global real economic activities interfere with monetary policy intermediate targets and, by extension, the ultimate targets. While existing literature has established theoretical Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models on how oil price shocks affect nominal exchange rates in net oil exporting economies (see, for example, Allegret & Benkhodja, 2015), recent development on rising hyperinflation in Nigeria amidst exchange rate unification and changes in its regime necessitated by depleted external reserve buffers, highlights the role oil price shocks could play in intermediate monetary policy target adjustments.

To date, not many studies have comprehensively examined specific aspects of shocks from the current demand for oil propelled by fluctuations in global economic activities. Specifically, there is a lack of evidence on the response of monetary policy targets to oil price shocks under a managed exchange rate regime based on the disentangled oil shocks and global economic activities computed by Kilian (2009). Despite its potential impact on the central bank’s ultimate targets (achieving price and output stability), little is known about the impact of oil-specific price shocks on monetary policy targets under a managed exchange rate regime in a net oil exporting country. Furthermore, current literature focusing on commodity price shocks and monetary policy targets, including Drechsel & Tenreyro (2018) and Coletti et al. (2021), gave prominence to nominal commodity price shocks and failed to investigate real commodity price shocks and the associated real shocks arising from global economic activities. This study will address this knowledge gap overlooked by the existing studies.

In terms of methodological contribution, this study extends Kilian’s (2009) earlier application of the structural unconditional dynamic simultaneous model. This paper applies a structural dynamic model with a conditional Time-Varying Parameter (TVP), accounting for the time dependency of the intermediate policy parameter, in line with Nakajima (2011).[1] The application of this method justifies variation in the threshold of intermediate policy variables over time under a managed exchange rate regime when the central bank discretionarily decides to adjust a new threshold by devaluing the currency to protect its external reserve from depletion.

The key message in this paper is that, for a net oil exporting country under a managed exchange rate regime, specific shocks from real oil prices and global real economic activities have a distortionary effect on monetary policy intermediate targets (as the exchange rate appreciates beyond its natural level). Under this circumstance, the empirical evidence shows that the ultimate target of low inflation is easily achievable in a relatively shorter time horizon. However, this is at the expense of declining domestic output growth, which is partly because the domestic non-oil sector will lose price competitiveness because of the over-valued domestic currency. Thus, persistence in the output fall progresses in the presence of rising real oil prices and expanding global economic activities. Consequently, to compensate for the domestic output fall, import could necessarily rise, which is symptomatic to the Dutch disease syndrome. This finding has potential benefit for the central bank on the ongoing impact of real oil price shocks and the associated shocks from global economic activities on its monetary policy targets, should it intend to maintain the just exited managed exchange rate regime. This paper contributes valuable insights for stakeholders by providing the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) with a deeper understanding of the issue that exogenously affects its monetary policy intermediate and ultimate targets. This could lead to practical application and policy changes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section II describes the data used in the paper. Section III specifies the TVP-VAR model. Section IV presents and discusses the result and Section V concludes the paper.

II. Data

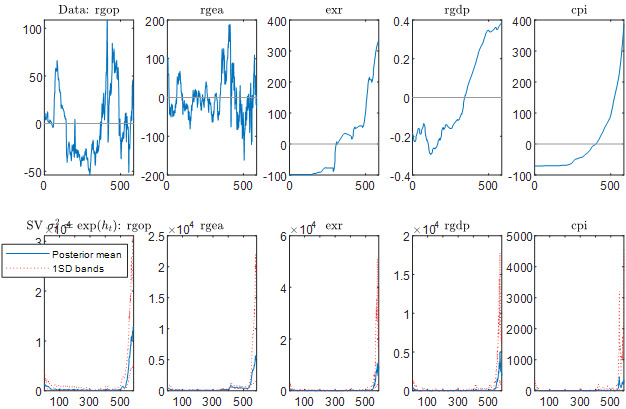

Monthly data on real oil prices were obtained from the Energy Information Administration. The global real economic activity index data was drawn from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Dataset on Nigeria’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) was obtained from the CBN Statistical Bulletin. Real Gross Domestic Product (RGDP) and official exchange rate datasets were from World Development Indicators. The RGDP was log-transformed to normalize the series, while annual frequency observations were converted into monthly for the exchange rate and RGDP series. The stochastic properties of the converted series before and after the conversion were tested using the Augmented Dickey Fuller test to ensure that the properties did not change. The unit root tests were all I(1), except CPI which was I(0).

III. Empirical Model

The empirical specification of the TVP-VAR in this paper follows Nakajima (2011) as expressed in equation (1):

yt=ct+β1tyt−1+…+βstyt−1+ϵtsuch that ϵt∼N(0,Ωt)

where is a 5x1 vector of observed variables, and are 5x5 matrices of TVP. is a time dependent covariance matrix. The decomposition and diagonalization is given by: and represents the lower triangular matrix, whose diagonal elements are all one, where is given as

represents set of vector row of while is a stacked vector row that captures lower triangular elements and where =ln The TVP assumes a random walk as defined in equations (2), (3) and (4) for the relevant parameters and elements:

βt+1=βt+ξβt,

αt+1=αt+ξαt,

ht+1=ht+ξht,where (εtξβtξαtξht)∽

The specified model was estimated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) based on the Bayesian method. The optimal lag and random seed were data determined, while the number of iterations was set at 10,000.

IV. Result and Discussion

Table 1 presents the estimates of the TVP-VAR model, including the mean values of the posterior distribution, the standard deviation of the parameters from the mean, the Geweke statistics and the inefficiency factor.

The results show that the mean values of the posterior distribution of the estimated parameters in the model fell within the 95% confidence interval, and the deviation from the mean values is negligible with a maximum deviation less than 0.08, while Geweke statistics were found to be greater than 10%, suggesting that the null hypothesis that the estimated parameters converge to a posterior distribution cannot be rejected. The statistics indicate that the estimates are effective and robust to the sample. The results show that all factors meet the sampling condition in the MCMC with 10,000 iterations.

Figure 1 shows the plot of autocorrelation, sample path, and posterior density of the TVP-VAR model. The plots indicate that the autocorrelation function dies off rapidly for most of the estimates, while the sample path shows the evolution of the stochastic volatility in the model and plots of the posterior distribution appear to be approximately normal.

The results of the TVP-VAR are presented as an impulse response function in Figure 3. The results show the response of three monetary policy targets to oil supply and oil demand shocks underlying the real oil price and global real economic activities (demand for industrial output). These targets are the nominal exchange rate (an intermediate target), price stability, and output growth (the ultimate targets). The figure comprises of two rows: the first row indicates the response of the monetary policy targets to real oil price shocks, whereas the second row shows the response of the monetary policy targets to global aggregate demand shocks.

The result in first row shows that the short- and long-run dynamics in monetary policy targets of the CBN under review are all negatively connected to real oil price shocks, while global aggregate demand is positively connected to real oil price shocks. The potential existence of a positive connection between real oil shocks and inflation is observed but short-lived in the long run. This suggests that the possible Philips curve relation between inflation and output gap collapses in the short run, and its re-emergence is unstable in the long run due to the rise in real oil prices. The negative and unstable output growth implies the possible lack of price competitiveness of other non-oil exports due to the positive real price shock. Furthermore, a fall in the exchange rate denotes appreciation of the naira relative to the dollar, signifying that positive oil demand shocks accrue external reserve buffers, which contribute to the over-valuation of the naira, in turn increasing import and shrinking output growth. Therefore, the central bank loses its ultimate target of output growth but achieves low inflation due to an overvalued domestic currency resulting from the real oil price shock. The increase in imports is believed to be triggered by the decrease in competitiveness and sharp fall in the level of domestic output, which constitutes a Dutch disease syndrome.

Second row shows the response of the monetary policy targets to global aggregate demand shocks. While short- and long-run dynamics in the real economic activities appear to approximate the real business cycle. The results indicate that real oil price shocks have a procyclical effect on global economic activities, which signifies the manifestation of precautionary crude oil demand in net oil-importing countries. This is consistent with Kilian (2009) and Alquist & Kilian (2010). The results reveal that the exchange rate and output are negatively connected to global economic activity expansion in both the short and long run. The negative response of the exchange rate is indicative of appreciation in the local currency, implying that as the global demand rises, the CBN discretionarily uses the external reserves accruing from the real oil price shock to keep the intermediate target above its actual value under the managed float exchange rate regime operated during the period. Essentially, the effort in managing the exchange rate will not allow it to adjust to its actual value when global demand rises. This relative short-term stability demonstrates appreciation against the dollar in the long run, and it continues until the level of external reserve depletion can no longer sustain the exchange rate at the existing threshold. Consequently, the central bank shifts to an upper threshold by devaluing the currency. The intermittent adjustment in the exchange rate depends on the frequency of expansion in global economic activities (output from industrial activities) and the corresponding real oil shock associated with it, which eventually passes through to inflation. Meanwhile, the negative response of domestic output to global demand shocks in second row further reinforces the lack of competitiveness in non-oil exports and the rising level of imports in Nigeria that underpins the Dutch disease syndrome. The results also show a short-run positive connection between inflation and global demand shocks. However, the results show a negative connection in the long run. Perhaps, the declining domestic output translates into negative supply shocks due to demand pressures arising from the output fall. Nevertheless, the long-run negative effect of the shock on price level displays the induced appreciating effect of the monetary policy intermediate target.

The results of the empirical TVP-VAR, therefore, reveal that, for a net oil exporting country under a managed float regime, shocks from real oil prices and global real economic activities could have a distortionary effect on monetary policy intermediate target; that is, the exchange rate appreciates beyond its natural level. Under this circumstance, the empirical evidence shows that the central bank’s ultimate target of low inflation could be easily achieved, but at the expense of realising the ultimate target of domestic output growth because the domestic non-oil sector will lose price competitiveness. Thus, persistence in the output fall progresses in the presence of rising real oil prices and expanding global economic activities. Consequently, to compensate for the domestic output fall, imports will necessarily rise. What occurs in these circumstances is believed to be characteristic of the Dutch disease syndrome.

V. Conclusion

This paper estimates the effect of oil-specific demand shocks on three monetary policy targets: exchange rate, output growth, and price stability. Having controlled for global demand for crude oil with the real global economic activity index, the effect of real oil price shocks on these targets was disentangled using restrictions in a TVP-VAR framework. For the period under review, the empirical analysis uncovers a negative link between oil-specific demand shock and monetary policy targets under a managed float exchange rate regime. This result demonstrates the substantial influence of oil price shocks, first, on the intermediate monetary policy target and, subsequently, on the ultimate targets in a net oil exporting country. Therefore, this paper concludes that appreciation of the intermediate monetary targets attributed to the oil price shock deflates the economy while shrinking output in the long run.

This class of empirical model addresses the Lucas critique